Learning Python: Action

Action dictates data and program flow. In my old Liberty BASIC programs, I feel lost in the action after years of not writing any.

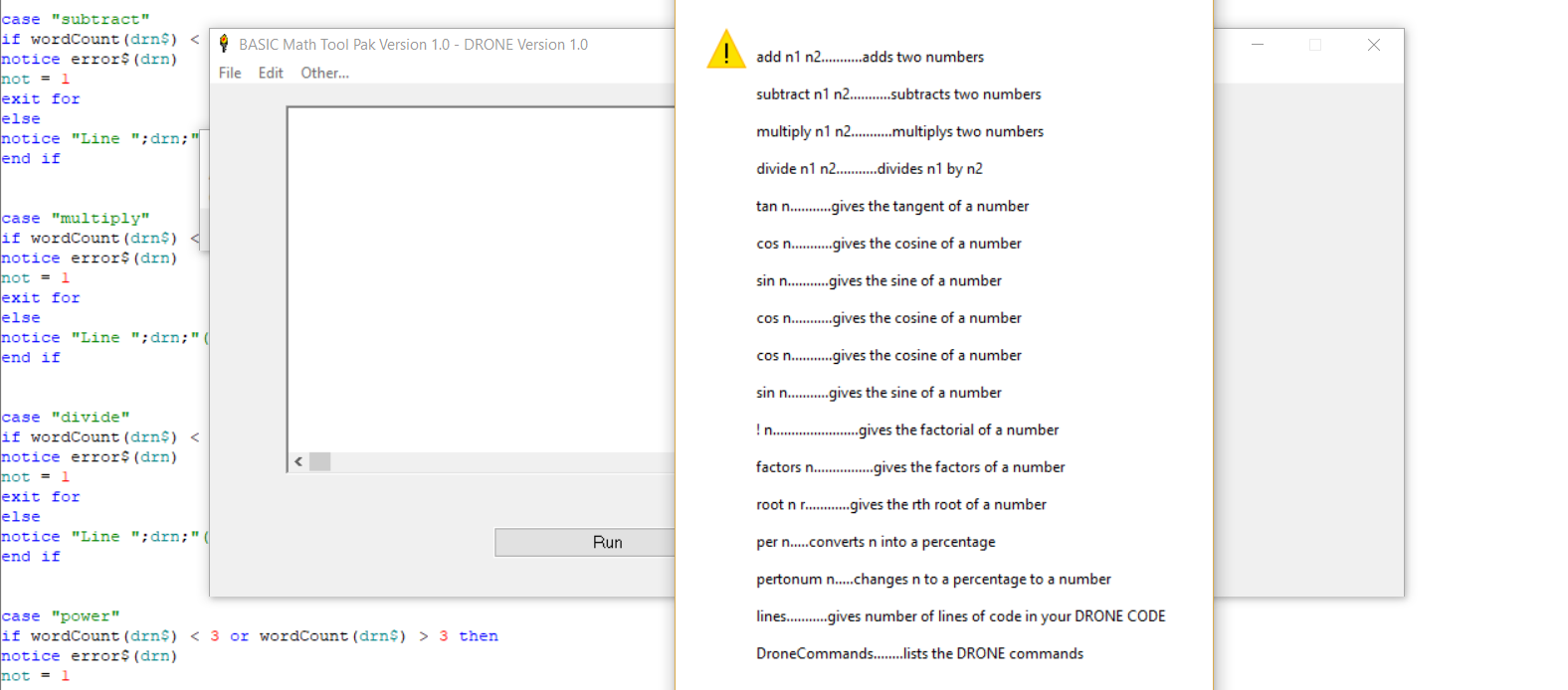

Inside of my math program, I wrote a small language called DRONE.

Maybe one day I will learn it again, but for now, I am focused on Python.

Without action, our data from the last post will sit and collect imaginary dust. To counter this would require ways to access, change, and use our data.

Accessing Data

In Python, []s are used to access sequence data such as list and dict.

coolThings = ['Ice', 'Snow']

funCityByState = {"CA" : "Los Angeles", "VA" : "Sterling", "NC" : "New Bern"}

secondBest = coolThings[1]

bestInVA = funCityByState["VA"]Sequence data is sliceable with [begin:end]. Either boundary can be left out to grab the rest of the list in that direction. The element at index end is not included.

coolThings = ['Ice', 'Snow', 'Rain', 'Water']

bestThings = coolThings[1:]

# Grabs all elements after and including index 1 ("Snow")

comparableThings = coolThings[:3]

# Grabs all elements before index 3 ('Water')New elements can be added to our sequences using append() for list and [] for dict.

listNames = ['coolThings', 'bestThings']

listNames.append('comparableThings')

flights = {"2016" : 2}

flights['2017'] = 5Modifying Data

An eye into our Python box would be useful. The print() function shows data in a console. We can now see changes in data.

age = 18

age = 19

print(age)

# -> 19The int is supposedly immutable. What is happening here? The age variable points to a reference object that does not change. Any change to age creates a new reference object with that changed value. To see this behavior, we can check each object’s unique number using id().

age = 18

print(id(age))

# -> 1862560144

age = 19

print(id(age))

# -> 1862560160

# age points to a new object now

# Lists are mutable, unlike int

# Mutable data does not juggle objects

coolList = ["Ice", "Snow"]

print(id(coolList))

# -> 48607480

coolList.append("Rain")

print(id(coolList))

# -> 48607480

# coolList points to the same objectThere is an upside to this behavior. If you pass an immutable variable to a function that messes with it, the original variable will not be changed. This preserved immutability can be tested by writing our own functions.

Functions

Python uses def to declare a function. Like most languages, arguments are comma-separated within the parantheses and return is used to return data.

def blipBleep():

return "blip bleep!"

print(blipBleep())To test the immutability of int, we can write a function that tries to alter one.

def addFive(input):

input = input + 5

ourInt = 10

addFive(ourInt)

print(ourInt)

# -> 10A common function to write is one that sorts a list of numbers. We need logic to sort numbers.

Logic

Logic directs the flow of the program based on our data. The most common directors are if and for as well as their many variations. Python’s if statements require a colon, like functions, and use == for equality.

if 5 > 3:

print("Hey, this should print!")

if 3 == 3:

print("This should print too.")

if 5 < 3:

print("This one won't print. Welp.")The for loop in Python grabs from a range of elements using in rather than counting up to (or down from) a boundary.

funWords = ['Kerfuffle', 'Alabaster']

# word holds each element in the proposed list

for word in funWords:

print(word)

# -> 'Kerfuffle'

# -> 'Alabaster'

# You can even iterate through a string

place = "Venice"

for letter in place:

print(letter)

# -> "V"

# -> "e"

# -> "n"

# -> "i"

# -> "c"

# -> "e"To imitate boundary loops, the range() function proves useful. This style gives you the index of the element.

for x in range(0, 2):

print(funWords[x])

# Note: range() function has exclusive end boundaries.

# x never becomes 2.

# We can imitate stepping size with

# the third parameter in range()

for evenNumber in range(2, 10, 2):

print(evenNumber)sortNumbers()

Let’s build a function that sorts numbers. The function should take in a list of numbers and sort order. Mutable data should not be altered. To achieve this, we will copy our input into a new variable nums using the list() function.

def sortNumbers(numberList, sortOrder):

nums = list(numberList)To go the bubble sort way, we need to compare each number to other numbers in the list. If one number is larger or smaller than another, depending on sort order, it will be swapped with the other number.

First, we need a loop that grabs each number. The len() function returns the size of a list which is useful for our boundary loops.

def sortNumbers(numberList, sortOrder):

nums = list(numberList)

size = len(nums)

for firstIndex in range(0, size):The function needs a second loop of numbers for comparison. This one selects every number except the one we are already on.

def sortNumbers(numberList, sortOrder):

nums = list(numberList)

size = len(nums)

for firstIndex in range(0, size):

for secondIndex in range(firstIndex+1, size):Comparison can now take place, but the function should allow sorting from largest or from smallest. sortOrder is one of our parameters. If it is 1, sort by largest. Any other value will sort by smallest. The else director splits the function’s direction.

def sortNumbers(numberList, sortOrder):

nums = list(numberList)

size = len(nums)

for firstIndex in range(0, size):

for secondIndex in range(firstIndex+1, size):

if sortOrder == 1:

# Sort by largest

else:

# Sort by smallestTo sort by largest, the element at firstIndex should be swapped with the one at secondIndex when needed. We used a variable tmp to hold the value before switching the values.

def sortNumbers(numberList, sortOrder):

nums = list(numberList)

size = len(nums)

for firstIndex in range(0, size):

for secondIndex in range(firstIndex+1, size):

if sortOrder == 1:

if nums[firstIndex] < nums[secondIndex]:

# firstIndex element is smaller?

# Push it up the list

tmp = nums[secondIndex]

nums[secondIndex] = nums[firstIndex]

nums[firstIndex] = tmp

else:

# Sort by smallest

return numsThe same swap can be performed for sorting by smallest with a change of inequality sign.

def sortNumbers(numberList, sortOrder):

nums = list(numberList)

size = len(nums)

for firstIndex in range(0, size):

for secondIndex in range(firstIndex+1, size):

if sortOrder == 1:

if nums[firstIndex] < nums[secondIndex]:

tmp = nums[secondIndex]

nums[secondIndex] = nums[firstIndex]

nums[firstIndex] = tmp

else:

if nums[firstIndex] > nums[secondIndex]:

tmp = nums[secondIndex]

nums[secondIndex] = nums[firstIndex]

nums[firstIndex] = tmp

return nums

numbers = [99, 3, 45, 60, 20, 23, 22, 4, 8]

print(sortNumbers(numbers, 0))

# -> [3, 4, 8, 20, 22, 23, 45, 60, 99]

print(sortNumbers(numbers, 1))

# -> [99, 60, 45, 23, 22, 20, 8, 4, 3]Not the prettiest or fastest function, but it is worthwhile practice. A moment spent Google searching reveals Python has a built-in function called sort(). Fundamentals are important, and I plan to continue strengthening them, but many functions have already been written. How do we use these?

Importing

To import, use the import keyword and the module name. The dir() function shows all functions of a module.

# Built-in Module called 'math'

import math

print(dir(math))

# -> *huge list of math functions*You can also grab specific functions (or all using * as a wildcard) from a module using the from keyword.

# import sqrt() from math module

from math import sqrt

print(sqrt(36))

# -> 6.0Conclusion

Basic tasks in Python such as accessing or changing data, creating functions, and using logic are now possible. I feel comfortable with the basics but digging deeper shows I cannot cover everything in one blog post. For example, I did not cover class, del, user input, finally and more.

The next post will be about basic Python language conventions. While that wraps up the three basic linguistic parts, I will practice and write more Python. There is more to discover in this intuitive and inviting language.